◡◶▿ Supply No.1 | Emma Rozanski, fast slow filmmaker

🤠 ...on building a rhythm & two years with Béla Tarr. A structured interview on filmmaking technique & the cineaste life with the writer-director. Plus: Perfumed Nightmare in London | UPV Supply No.1

Dear eternal filmmaking students. We are amid a series of posts on Renovating the Home Movie. You know that. But this week, I’m delivering something different. The first in an occasional series of filmmaker interviews. Okay!

That’s right: last class, I wheeled out the TV trolley for a bit of Frampton and Wieland, and this week, I’m wheeling out a supply teacher. Her name is Emma Rozanski.

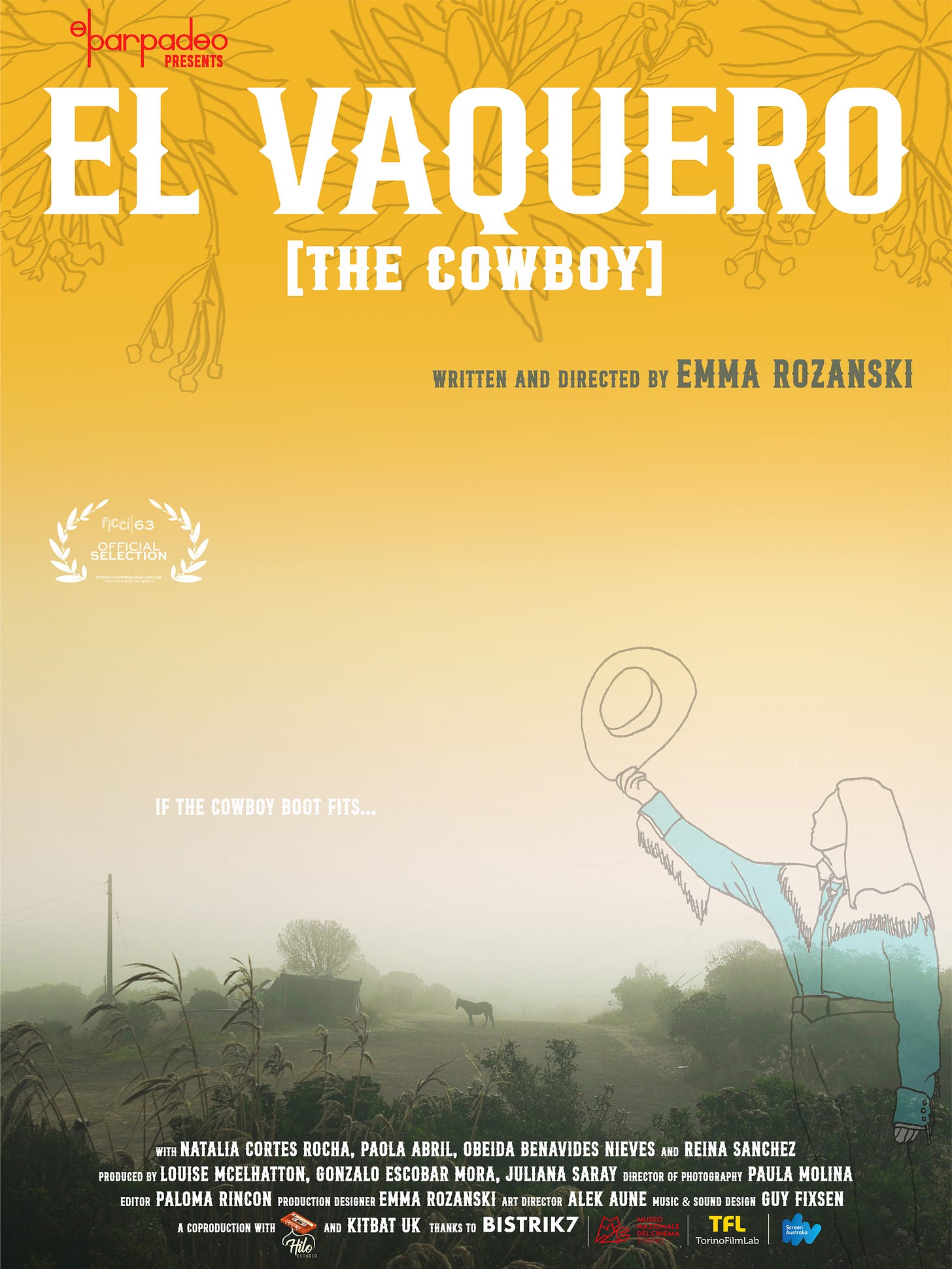

Rozanski’s second feature as writer-director, El Vaquero (2024), just won the Best Narrative Feature Prize at the Tacoma Film Festival in Washington. Great! Well done.

And El Vaquero is now playing at cinemas across Colombia. Rozanski will present it in person twice this week. In the Cinespiral Manizales on the 12th of November 2024, and the Cine Con Alma Cámara De Comercio in Pereira on the 14th, both at 7 pm. It continues in Bogotá throughout November.

We first met at Lawrence Boyce's Hull Film Festival in 2009. We became cocktail buddies. It was Rozanski who would alert me to the launch of Bèla Tarr's doomed film school in Bosnia. We became housemates in Sarajevo upon our acceptance to the Hungarian master's little community in 2013. Some called it a cult.

Like myself, Rozanksi was brainwashed to such a degree that she ended up marrying a classmate. Her husband, with whom she lives and works in Bogota, is a talented and weird filmmaker in his own right. Perhaps we shall hear from him another time. His name is Gonzalo Escobar Mora.

In today’s lesson, Rozanski will discuss:

🧙♀️ How to “allow for magic, but… plan for control.”

🐴 How horses show love in the movies.

⏱️ How to make a slow western when you’re constitutionally impatient.

👩👩👧 How her editing process involves slowly moving in with her editor.

Plus, the lesson that Rozanski carries with her from two years of study with Béla Tarr.

Please forward this interview to someone you know will appreciate it. And then make yourself comfortable. And please make Emma Rozanski feel welcome. Okay. Quiet now.

📹 Unfound Peoples Videotechnic | Cloud-based filmmaking thought. ☁️

🐦 Twitter | ⏰ TikTok | 📸 Instagram | 😐 Facebook | 🎞️ Letterboxd | 🌐 unfound.video

Allow for magic, but plan for control

I spoke to Emma Rozanski by videophone on 4th November, 2024. Quotes have been lightly edited and re-structured for succinctness, a quality that Rozanski holds dear. Rozanski has approved these edits.

Each of Emma Rozanski’s movies seems less choreographed than the last.

There were the clockwork performances of The Storymaker (Writer-Director: Emma Rozanski, 2009), her second short. The storyboarded psycho-architectural dérives of Papagajka (2016), her first feature. These movies and others work like wind-up boxes against which their players strain to the point of malfunction. But the lead actor of El Vaquero (2024) keeps her inner mechanisms to herself.

Rozanski’s characters have a tendency to shed their identities as they construct fantasy worlds for themselves. This is the shape of a Rozanski movie. But in El Vaquero, that fantasy space is rural and at least partly anti-social. And so, the lead character need perform only for herself.

Bernicia finds a lost horse and a cowboy shirt. She retreats from family life to the wilderness to try them on for size. This plot allows Bernicia an intimate space and the right to be inscrutable on screen. It is a right she declines in moments of private performativity: tipping the cowboy hat of an ornamental dog, prodding a saloon bathroom door, holstering her wash rag. The latter action already seems to have evolved from “performance” to “habit.”

However, despite El Vaquero’s organic feel, Rozanski did not entirely re-wild her actors.

“I always plan a film based on the assumption that I’m going to need to heavily direct and edit an actor to be who I want them to be in the final film,” Rozanski tells us. “I think that way of thinking is partially because I know my budget limits me a lot with casting and partially because I’m not experienced enough yet, I think, to trust actors as much as I should.

“But also, you know, maybe they’re a little untrustworthy as well.

“I always plan for that eventuality, but then if an actor is capable of bringing me other things, then inevitably they will take the character and make them their own. Magic can happen when you allow actors to do that.

“I like to allow for that magic, but I plan for complete control.”

Working with horse

El Vaquero (Writer-Director: Emma Rozanski, 2024) is a sort of western. The lead character, Bernicia, decides it’s a western when she finds an abandoned horse and begins to remodel herself as a cowboy. That’s what El Vaquero means. “The Cowboy.”

Rozanski agrees that a guiding theme across her movies is of characters shedding their identities and constructing fantasy worlds for themselves. Sometimes, there is another person to coax this character along. For better or worse. Here, there is a horse.

The horse does not coax or gaslight Bernicia into becoming a cowboy. Instead, the shedding of identity and construction of a fantasy world emerges from the physical and emotional relationship. Just like in a love affair.

So, El Vaquero is a sort of love story. But you don’t see the horse love her back. Or do you?

“I think you see the horse love her back,” Rozanski tells us. “I think when she plays the harmonica, the horse responds to that. Definitely, on the shoot, we all had a little tear in our eyes because that horse was definitely hearing. The ears and the tail… Just a very, very subtle actor.

“But I think that’s the way it is with certain animals. It’s maybe one-sided, and we just imagine the other side. I think that’s enough for Bernicia.”

The horse was not a professional actor. She was a workhorse. A retired one! Getting her to follow the blocking was not difficult. But to affect love on cue? Not possible. “Most of the time, the horse is like: ‘Okay, this is all great, guys, but where, when can I start eating grass again?’”

On the other hand, the horse could be demonstrative about her antipathies.

“The only time she got agitated was where this guy in one of the locations we were at, not one of the crew - I was helping to saddle her up, and he was quite an aggressive guy, with a very macho attitude to life in general. And she did not like him. She could sense him.

“That day, after he had saddled her up, she was not cooperative. That was the only day. When she sensed this unkind, aggressive person.”

Perhaps love - horse love at least - is best expressed through ‘being’ together: occupying those fantasy spaces; entertaining those new identities. That’s what happens in the movie. It’s what happened on set.

“The DP had riding experience. So she rode her to the set one day. And the art director would hang with her a lot and bring her to set. We all took turns wrangling the horse, basically.

“She was very sweet, very calm. She would just stand as long as she had grass.”

A fast slow film

Is Emma Rozanski’s El Vaquero a fast film or a slow film? It depends on what type of horse you are. The movie trots at a meditative pace. But the shots are brief and clipped. This is clipped slow cinema.

“My editor and I actually called this film a slow fast film, or fast slow film,” Rozanski tells us. “We were very aware that that was what we were doing. Because that was the film I wrote. There’s not really a possibility for it to be faster.

“There was definitely a possibility for it to be slower, but I don’t have a lot of patience for such things. So, the pace is dictated by my patience. Some people find my films very slow, and some people find them too fast, which is why I feel like I’m a little in the middle of those worlds quite a lot.”

In one scene, the main character, Bernicia, argues for a slower western: “I wanted to see more of the cowboys just riding and watching the landscape,” Bernicia says, after just sitting and watching an old western on DVD. The pace and self-reflexivity of El Vaquero bring the acts of movie-making and -watching back to an ambient or social space. The scene of the women watching the old western has an edit suite mood.

“I moved in with my editor for this film,” says Rozanski. “I would stay with her for two-week blocks, and then she would do refinements. And then, I would come back, and we would do intense work on the performances or structure. But we laugh the whole time.

“The editor has to be really intelligent, has to really know a lot about film, and have watched a lot of film. Because you’re constantly having conversations about that, and putting yourself in different mindsets of who will see it, and what way.

“And that ultimate rhythm will be what you two are in your relationship together, because you’re sitting there together, feeling time together. It’s an amazing thing. And to do it alone would be so not fun.”

But the edit - and the pacing - begins on set, in Rozanski’s head, as her instincts respond to what she sees in the moment of filming.

“You have to split your personalities, especially because I also produce, and I also have a bit of a control freak AD part of me, which I had to do much less on this film because I now have an amazing AD. But that personality trait is still present. Always. And sometimes I have to actually shut them up a little, if they get in the way too much and remind myself that I have to have the main feeling-directors head on during shoot or during a take.

“But occasionally, I will have a stopwatch, because I also theoretically know how long a monologue should be for me. And I know that if it surpasses a certain point, then the actor’s being too slow. I don’t think they generally notice that that’s what it’s for.”

It is no stretch to imagine the rest of the crew standing behind the camera, watching Rozanski with her stopwatch. Gambling between themselves on whether the actor will make it to the end before they drift into the realm of slow cinema. Rooting for the actor or for their preferred pace.

The terrible assembly

Her peers lock themselves up alone to edit the footage they directed. They put their own sticky snack fingers all over the controls. But Emma Rozanski hands her footage to an editor. And waits for it to take shape before joining in. Even then, she rarely touches the buttons.

“I love working with an editor, because if I’m operating the editing process, then I’m not not able to step back and look at the film properly,” Rozanski tells us. “I’m just not capable of it. It comes back to: I don’t have the patience for it. And I need to be connected to my feelings of time, which means I have to sit back.”

For Rozanski, it is necessary to conduct her thoughts and feelings through a trusted colleague.

“I had an amazing editor for this film, Paloma Rincón,” says Rozanski of El Vaquero (2024). “She’s Colombian. And for Papagajka [2016], I had an amazing editor, Kostas Makrinos. I loved working with both of them, because we had the same sense of humour and because we’re spending a solid month or two months together side by side.

“It’s such a fun time, you know? And it has to be because it’s so intense, that relationship. It’s the most of anyone in a film, more than actors, more than everyone, because they’re your final co-writers.

“For me, that’s necessary. You have another point of view.”

Rozanski lays out her editing process for us. The director:

completes an edit script after filming, incorporating changes that happened during the shoot.

hands it to the editor along with the rushes and says, “Good luck.”

waits for the editor to complete a first assembly.

provides “a round of very broad notes because the first assembly is usually terrible, inevitably.”

waits again for another pass while the big notes are addressed, and

decides that “that’s the point at which I’ll sit down with them, and then I really won’t leave their side. But we’ll do it together.”

Put like that, the editing process sounds warm and enjoyable. Or awful! Depends on the person. And the other person!

A Hungarian cross-examination

Emma Rozanski studied filmmaking with Béla Tarr in Sarajevo from 2013-15. It was under Tarr’s mentorship that Rozanski made her first feature. As film school principal, Tarr did not encourage direct schooling of established filmmaking methods. Instead, he fostered certain sensibilities while drawing out the potential unique to each student.

“I always carry Béla [Tarr] with me during a film, because he had a very firm yet special way of intensely cross-examining my intentions and my will to make the choices I was making,” Rozanski tells us, “- that deep and necessary justification of choices gives a film a voice of its own, and it also carries me as a director and as a person, through a film.

“I always felt Béla was testing that strength- and if we couldn’t defend every choice, then the choices should be changed or discarded.

“That’s a very important message, I think, in filmmaking.”

Thank you Emma! Please leave your pass at reception on the way out.

Students, you can leave your thoughts, queries, and exercises from this week’s lesson in the comments.

Perfumed nightmare

Tonight in London (11th November 2024), there’s a rare chance to see Kidlat Tahimik’s 1977 film, Perfumed Nightmare, out and about. A truly wonder-ful film some of you (but not many) may recall from our IRL module on Mythology of the Self. It plays at Metroland Studios in Kilburn at 18.30, curated by Beansprout Film Club.

Says the screening blurb:

“Produced, directed, and starring Tahimik, Perfumed Nightmare is a genre-defying exploration of colonial legacies, modernization, and cultural self-determination. Set against the backdrop of 1970s neocolonialism, Tahimik’s film delves into the “nightmares” that emerge when a culture encounters – and resists – the forces of Western “progress” and capitalistic expansion.

Following the screening, we’ll open up a space for reflection and discussion, inviting participants to explore the layered meanings and provocations in Tahimik’s film.

Beansprout Film Club is a space for East and South East Asian people to better understand our shared identities, histories, and cultures. Through film, food, and discussion, they hope to strengthen solidarity between East and South East Asian and other global majority communities in London.

Please bring snacks to share!”

Snacks!

Next week, we’ll continue our autumn program of micro-essays on Renovating the Home Motion Picture. We’ll talk about the diary film. Great! Nice.

Class dismissed,

~Graeme Cole.

(Principal)