◡◶▿ SOFT04 | Automatic filmmaking

🎰 How to Make a Movie in Your Sleep; or, Notes on the Roomba® as Cinematographer. Plus: Piccioni. Wegman. Wertmüller. | Imaginary Software of the Filmmaking Future Week 04

Hi hi! Sorry, students. Due to issues, I’m a little late for class today. Rare! Unusual.

I know many of you in mainland Europe wait for this email before starting your Monday morning croissant. So, without further ado, let’s flashback to last week’s pastry. During which, we covered how:

Despite dreams of generating entire careerloads of cinema at the press of a button, filmmaking software often begins with a corrective stitch or patch.

Even the slightest AI-generated stitch is irrevocably networked with a great mass of written, photographed, and recorded human culture.

Generating art with AI is a lot like knitting in the dark, except that your needles are wisecracking Pixar characters.

Your first word may be a belch, but the second adds context.

That sort of stuff.

Missed a week? Joined late? Don’t worry about reading these lessons out of order. Each functions independently. They are sent in a sensible sequence but hardly reliant on it.

In today’s lesson, we will discuss several categories of filmmaking software. Which is to say: types of coded instruction which you might feed into various types of hardware to ease the production process. (Or make it more difficult, if you prefer.)

In particular, we’ll look at:

🤖 Automatic filmmaking software. Programming basic software to produce your basic movie.

🍳 Automatist filmmaking software. Your subconscious thoughts evading the interference of your waking mind and, ideally, your producer.

🧮 Generative filmmaking software. Hoping and praying that sums have souls.

🎛️ Synthetic filmmaking software. Smooshing a variety of materials together to make them seem like something else.

And how you might use or abuse these software types.

These software categories overlap, overflow, or nest within each other. And they’re certainly not the only ones! But perhaps we’ll take a little dash across a broader taxonomy of automatic filmmaking softwares later in the year.

Motion control

You can hear me deliver this lesson by scrolling up to the header and clicking Listen and/or the play ▸ button.

Motion control photography is an established technique for wrestling control from one human’s shoulders and re-installing that control at the fingertips of another.

The filmmaker and her cinematographer sit around a keyboard and program the perfect moves for the camera. And they feed this program into a robot camera operator. The program ensures that the camera maintains an identical frame from one take to the next. An identical frame relative to the natural and built topography of the surroundings.

Of course, that frame’s contents are subject to the whims of the freeform actor and global geomorphology. But the motion control filmmaker is usually the type to find ways to program those elements as tightly as possible, too.

Anyway, the idea is ultimate control. Cool! If appropriate. If thematically apt.

However, the filmmaker might use a motion control photography-like technique to devolve creative control. To devolve control to:

chance, or

indifference, or

unknown inner systems (including software spirits) or, indeed,

to the processes of global geomorphology.

Consider

Michael Snow’s exhaustive pre-programmed camera adjustments as alien-led anthropology;

Lars von Trier’s Automavision, a computer-randomised camera set-up (for which the software was credited as cinematographer);

Steina Vasulka leaving the video signal in charge.

The filmmaker might use a motion control photography-like technique to:

save on time or crew numbers,

explore less-human ways of seeing,

be lazy.

The motion control-type filmmaker might program other simple settings, such as triggered recording, auto-exposure, metered wobble offset, etc. At their most complex, such programs are considered ‘generative.’

But photography software does not generate material so much as it produces material automatically. The vital spark is not quite in the machine or in the numbers. The spark is in the sunrise or birdsong or exhaust fumes that trigger the camera into its pre-defined dance moves. And in the fingers that anticipate the best dance moves for the job.

And so, motion control-like techniques are not such an easy way to produce satisfactory results as they might seem. Everybody wants a recipe for easy filmmaking, but the automatic filmmakers have taken on the difficult job of concocting the recipes. The skill is no longer in completing a brief but in writing one.

Still, there’s no reason not to apply these techniques to any department of the conventional film production - providing the necessary software can be arranged.

Automatist filmmaking

Automatist filmmaking reflects the Surrealist ideal of divining creative matter from deep below the conscious mind. The human machine is operated by its secret software, which has, in turn, been programmed by - we must presume - entropy, society, diet, her parents, etc. The filmmaker writes or waves her camera around or hacks a CCTV system according to her primal compulsions.

The automatist filmmaker tries not to interfere too much with what comes out, however ill-advised this might seem.

Automatist-automated filmmaking

Automatic filmmaking is what happens when a human filmmaker sets up machinery to produce a movie or movie materials without further human control.

But with automatist filmmaking↑, the human filmmaker is the machinery.

In the future, it will be possible to combine automatist and automatic filmmaking to remove further effort from both practices. The filmmaker might route the natural data produced by her subconscious mind directly into an automated system. Her software talking to Its software.

This arrangement will better fulfil the aims of both the automatist and the automated filmmaker.

The automatist removes a further layer of human control. Whoopee!

The automatic filmmaker removes a further layer of work. Easy business!

However, these types of automatic filmmaking emphasise the question of control. And so, before the filmmaker devolves control to any external or internal software, she makes sure she has a good idea of what’s inside that software, that spell. Or how she will reprogram it to reveal itself.

Unless she’s just in it for the money. Or the entertainment!

Generative

Outside of filmmaking, generation is the production of physical, spiritual, or conceptual stuff on a vital or seminal level.

Generation may be a subset of production. Or just another word for it. But production has undertones of the basic or mundane. On the other hand, generation has a magical, mystical, even divine aura. This is despite the grotty nature of many generative processes.

Still, seen from a certain point of view, most of what goes on in the world is generation, really. The human animal doesn’t generate carbon dioxide until looked at as a carbon dioxide generator, although the trees may see us this way.1

Generative filmmaking

In the most common terms, a filmmaker generates an idea but produces a film. That’s what we say, right? The filmmaker provides a flow of vital concepts and the crew labours to furnish them with mundane but necessary physical matter.2

But generative filmmaking has long referred to a more particular area of production. The area of the autonomous generation of movie materials. The generation of materials following the initial design or programming of:

algorithms,

systems, or

rules.

To create with a code, such as a knitting pattern or DNA.

The filmmaker herself might take several steps to coax a generative process into action.3 But the generative system - the software, computer-based or otherwise - then runs on a set of rules. A set of rules so vital and authoritative that it might ‘rule’ the film set. Run the production without further intervention from the filmmaker.

Instead, the filmmaker might go for tea or join the crew in fashioning whatever material elements the system requires of them.

Generation inevitably leads to successive generations. And further cups of tea. And further tasks. Therefore, to coax a generative filmmaking process into action is a heavy responsibility. (Same goes with generating heirs or carbon dioxide.)

Generative filmmaking refers mostly to the production of actual physical, audio-visual, or conceptual matter. The making of more stuff. Generation! But sometimes refers to the pre-programming of recording apparatus (e.g., motion control↑) or the adjustment of existing materials.

But generative filmmaking can also refer to the arrangement or reproduction of existing materials:

When software chooses from the countless scenes of Guy Maddin’s Seances (2016) and rearranges the chosen scenes into an infinite archive of potential movies.

Ditto Eno (Dir: Gary Hustwit [Chance Operations], 2024). Eno! Of course.

And then there’s the ‘guitar pedal’ school of generative filmmaking. The algorithmic modulation of matter that’s being produced anyway. The systematic adjustment of existing movie materials, regardless of whether they were produced under the enthusiastic control of the filmmaker/her human colleagues or by software/generative processes.

Examples:

the actor performs a sad line sadly, and the filmmaker varies the material qualities of the performance using a set of parameters, physically or with computer software.4

The filmmaker adds steaminess to a sauna scene, not by generating more steam, but by dialling up the steaminess (or any other variable that might achieve this aim).

The generative software locates the seed from which it generated a particular element

It goes to work on it in its own mad, deeply rational way.

(Steered, perhaps, with mad despair by the generative filmmaker.)

Sick algorithm

And what happens if an algorithm gets sick?

The everything pen

Most filmmaking is synthetic; filmmaking is the synthetic art. At least among the seven arts when considered in their fundamental senses.

Filmmaking always involves and thrives upon the putting together of things. Things from disparate sources. Smooshing them together and resolving them into a cohesive flow.

Perhaps the filmmaker might consider the process of synthesising movie materials with generative software to be synthography. This term is often used in connection with synthetic photography and image-making. But for the filmmaker’s purposes, it is a natural descendant of both cinematography (writing with movement!) and Alexandre Astruc’s caméra-stylo (camera pen).

Astruc identified the caméra-stylo as “a form in which and by which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they may be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel.” Beyond narrative and image: pure thought, expressed with the lightweight apparatus of the mid-century avant-garde.

Meanwhile, the synthographer can simply load her virtual pen with a cartridge of aggregated art history and scrawl her thoughts directly with movie ink drawn from a billion disparate sources. A disparate sauce, if you will.

The filmmaker might just splodge the sauce, the everything-ink, all over her cine-paper. There is probably a period of that for everyone, on receiving the everything pen! But after a moment of reflection, she guides her everything-pen according to her:

“thoughts” and “obsessions” (Astruc), or her

“flowing ideas, chains of obscure reason, thematic pulses, visual codes, visceral implosions, surgical syntheses of [her] current obsessions and fancies, and spontaneous warps of/associations between all of the above” (Nanneman).

But she cannot do so without smooshing herself in, too, and somewhat blindly, for better or worse.

Please share your thoughts, queries, and exercises from this week’s lesson in the comments.

Everything is in place and nothing is in order

You’ve probably heard that an incredible piece of new text-to-video software was unveiled this week. Important! A real game-changer, they say.

Unfortunately, I was too busy listening to the new release of Piero Piccioni’s soundtrack for Tutto a posto e niente in ordine (1974). Too busy to write about the new software.

Lina Wertmüller’s movie title translates as “Everything is in Place and Nothing is in Order.” After all, this is the filmmaker that also gave us The End of the World in Our Usual Bed in a Night Full of Rain (1978), A Twist of Fate Lurking Around the Corner Like a Street Bandit (1983), and Stuffed Peppers and Fish in the Face (2004).

The human species is going to be just fine!

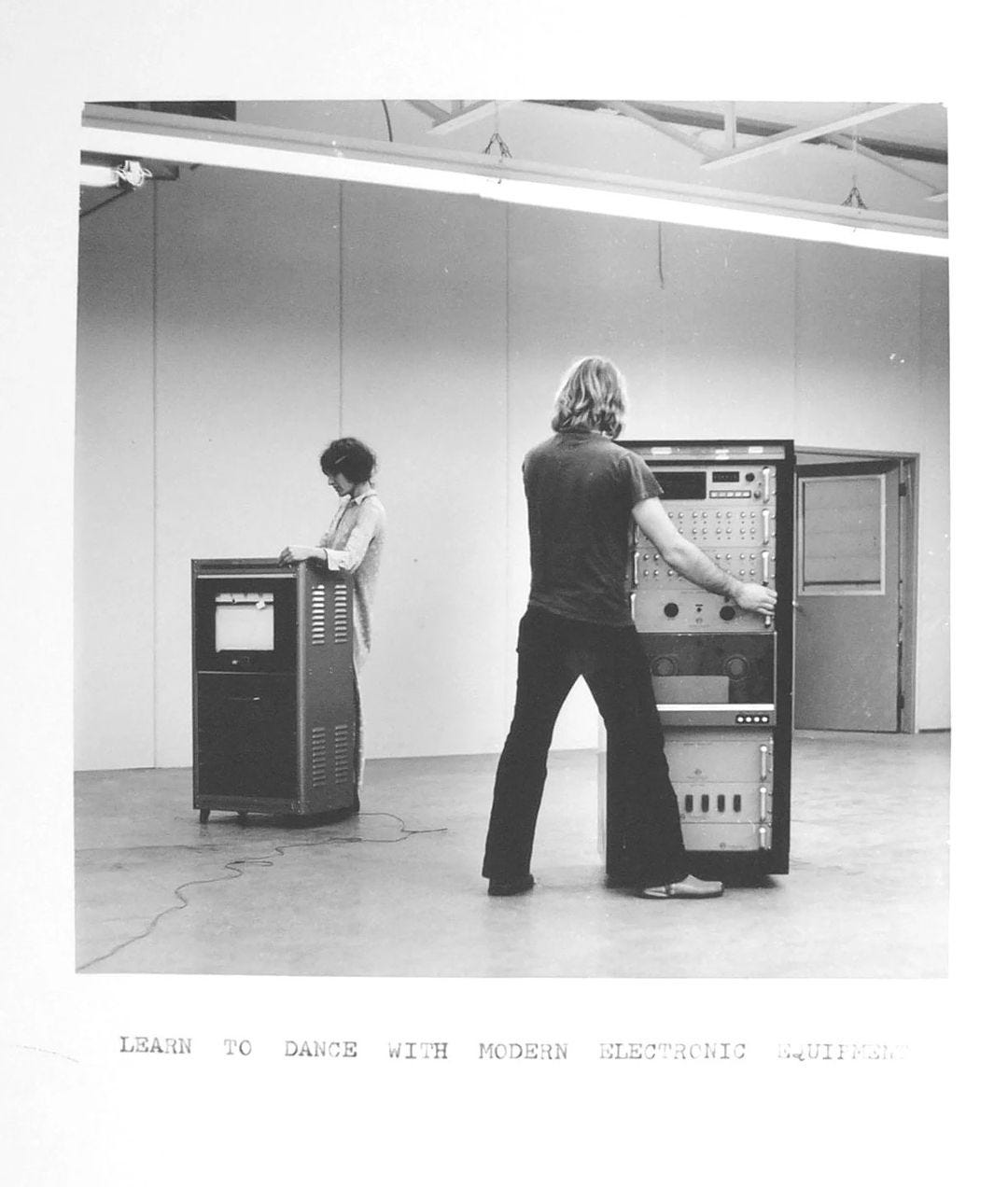

Learn to dance with modern electronic equipment

Seems relevant.

Next week, we’ll look at radical incompatibility, friction, toxic junk, and - time allowing - sentient .SRTs.

Class dismissed!

~Graeme Cole.

(Principal)

📹 Unfound Peoples Videotechnic | Cloud-based filmmaking thought. ☁️

🐦 Twitter | ⏰ TikTok | 📸 Instagram | 😐 Facebook | 🎞️ Letterboxd | 🌐 Website

Even decay can be generative. Most things are both, so it’s worth looking both ways when generating this or that.

The filmmaker doesn’t generate a superhero movie (unless deliberately using generative techniques). But she generates a superhero world and an implicit set of 130-minute audiovisual arrangements of the happenings in that world.

(as is often the case when generating this or that with DNA, for example.)

Once again, you can’t help but think that intimacy co-ordinators are either the biggest losers or the biggest winners in the age of generative AI filmmaking.