◡◶▿ AMAT09 | Shabbiness

The candle-wax on the cuff of the late-night poet-filmmaker. Plus: Guy Maddin’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. | Advanced Amateury Week 09

Hello! We’re welcoming a lot of new subscribers this week. Welcome! So, here’s a quick recap of what’s going on.

Unfound Peoples Videotechnic is a roaming absurdist film and video academy.

Every Monday, subscribers receive an email newsletter of micro-essays on the esoterics of filmmaking.

I’m the principal, failed-filmmaker-turned-bitter-guru Graeme Cole.

We’re adrift in a 12-week program called Advanced Amateury (AMAT), ‘Clumsy Loving in the Age of Competent Content.’

Don’t worry about reading these lessons out of order.

Each lesson functions independently.

They are sent in a sensible sequence but hardly reliant on it.

All the same, you can find the first lesson here if you wish.

Each lesson is, itself, an assemblage of independent but sensibly sequenced micro-essays.

We start each lesson with a quick recap. And here it is now.

Everybody comfortable? Here’s a recap of last week’s lesson, Faulty, in which we learned how:

A mistake could end anywhere - if you’re lucky, it will end in an accident.

‘Misfortune’ is an excellent word for removing blame from your set.

Hollis Frampton systemised misfortune, supposedly.

There are six categories of misfortune, according to Frampton: “metric errors, omissions, ‘errors’, lapses of taste, faking, and breaches of decorum.”

In today’s lesson, we will discuss:

🖋️ In filmmaking, clumsiness is a kind of handwriting - and often, there are several klutzes holding the pen at once.

🎷 In music, imperfection means authenticity, while…

🎭 … in movies, imperfections reveal the underlying inauthenticity of the filmmaking process.

🍰 A better world is possible, in which authentic clumsiness and shabbiness are broadly appreciated as legitimate and potent cinematic residues.

If somebody forwarded this email to you, please consider subscribing here:

And whatever your position in the email chain, please consider forwarding this lesson to someone who will appreciate it. This is a niche project and it mostly grows through word-of-(digital)-mouth.

Let’s begin.

Clumsy

You can hear me deliver this lesson by scrolling up to the header and clicking Listen and/or the play ▸ button.

Clumsiness has the effect of a sort of handwriting. The shape and underlying currents of clumsiness are particular to each individual’s body and mind. We recognise the clumsiness of a particular filmmaker from one of her movies to the next. A portfolio of clumsiness with recurrent motifs.

Clumsiness is abrupt. It disrupts flow. The audience expects a film to unfold according to a set of laws. The physical laws of the universe of the film, framed by the expectations established in the universe outside the film. Clumsiness disrupts the film universe’s flow. Which, in turn, jolts the universe in which it is contained.

These abrupt starts make it difficult for an audience to warm to a clumsy filmmaker’s work on the first viewing. Stop jolting me, thinks the audience. You’re so jolty.

But, when they recognise her clumsiness in subsequent movies, they may regard her hand with familiarity and affection.

An observant and affectionate viewer may even analyse this clumsiness. Analyse the unintentional but consistently fattened lobes and bowls of a filmmaker’s ‘handwriting.’ This viewer might understand the meaning of the filmmaker’s clumsiness better than the filmmaker herself.

Paired with attentiveness to the filmmaker’s intentional emphases, this interpretation of her involuntary clumsiness can make for deeper communication with the film’s ideas. Lovely!

This ‘clumsy filmmaker’ should also be considered legion. When a director or artist-filmmaker works consistently with the same clumsy DoP, actor, and continuity supervisor, the audience is treated to a chorus of clumsiness. The chorus of clumsiness repeats - or echoes - with variations on its theme from sheaf to sheaf of their collective portfolio.

What does it mean that these clumsy artists keep working together? Do they know? Do they care?

A bold word or phrase indicates that an instruction of this name and concept appears elsewhere in this module.

Shabby pop

Broadly: clumsiness is less unwelcome in pop music than in the cinema.

A lot of “normal” soul, rock, and pop music communicates through the deliberate inclusion of performance and production flaws such as:

stuttered beats,

strained notes,

instrument litter (string noise, sundry thunks and rattles),

vocal litter,

feedback and the sundry signs and symptoms of the apparatus’ digestive life, and

muffled lyrics.

These are common conventions across broadly appreciated music. These conventions signal the authenticity of the music. The authenticity of the musicianship, experiences, and/or the emotions of the front person, their band, and even their production team. The handwriting of the musicians’ feelings.

How curious! We accept the content of many of these songs to be fictional (or hypothetical), but their performance to be realer than real.

In the cinema, audiences are not so interested in the unfettered transmission of the artist’s authentic experience.1 In the conventional cinema, authenticity means deliberate attention to detail. Precision. Even if that requires precisely fabricated shabbiness.

The audience of a conventional film does not expect the director or crew to noticeably choke on their feelings or their protein bar. But what could be more human, more soulful, more romantic, more action, more science-fictional, more real, more cinematic, than a boom in frame? A plot inconsistency? A sneeze and a shush from somewhere behind the camera?

Patches

There exists an odd contradiction between pop music and movies.

In pop music, the production apparatus may ‘drift into shot.’ Apparatus ‘drifting into shot’ suggests authenticity. A direct line from the artist.

For example, conspicuous use of autotune suggests:

“I, your entertainer, am trying - but I can’t do this alone, for I am in considerable emotional pain,” or,

“Look at me! I found the robot effect in my studio, ha ha ha. Let’s dance.”

Success is just a gaudy frame for all your failures.

In the conventional cinema, the production apparatus should not ‘drift into shot.’ Apparatus ‘drifting into shot’ reveals the inauthenticity of the filmmaking process. There are exceptions:

Shaky cam in a fiction film.

Suggests that events are so live and unpredictable (and really exciting) that the camera operator didn’t even bother to unpack their tripod.

The lens flare↓. (Cinema’s answer to guitar feedback.)

Lens flares broadcast the (false) authenticity of shots that position the camera in outer space; or personal moments so touching that the camera operator must distract from their inability to communicate raw, unfiltered truth.

However - and it’s a big “however” - these flaws differ in essence from their pop music equivalents. In music, production flaws are used to draw attention to human foibles and limitations. In the conventional cinema, these flaws are falsified to patch over such limitations.2 The crew is covering their tracks.

Patching is a technique stolen from the amateur filmmaker. The joke is on the mainstream cinema, for they have failed to use the technique correctly.

The amateur filmmaker may also use ‘patches’ to cover holes in her work. But the patch itself evokes the hands of the crew member who cut the patch to size. The seams of the sewn patch should be visible. A hastily-sewn patch may:

Leave a trace of the meaning of the hole while allowing the audience to overlook the hole itself.

Create a charming kintsugi-type effect along with the aesthetic and philosophical values that the art of kintsugi nourishes.

Furnish the movie with an extra dimension, which the filmmaker may play with (and between) to her heart’s content.

In the amateur film, recording apparatus may drift into shot. Drift into shot visibly or by implication. And so may the operator of this apparatus. Visibly or by implication. The filmmaker's love for this shabby crew member makes them a welcome presence in the film.

The realistical fallacy

The realistical fallacy refers to a common belief. A common belief held by filmmakers and upheld by the audience. The belief that:

certain falsified forms of clumsiness or shabbiness make a film more real,

(and that ‘real’ is a good thing), while

most forms of authentic, involuntary clumsiness or shabbiness make a film less real.

The audience is conditioned to understand that they are at the hands of a master manipulator. An illusionist. And the audience would prefer to forget about it. Hmph!

Slick filmmaking allows audiences to “suspend their disbelief.” Suspend their disbelief that these events could unfold before them in a dark room in two and a bit dimensions. The slick application of a peppering of ersatz shabbiness is more than permissible.

But there exists a quiet minority of folk who can’t achieve “suspension of disbelief” in a film if it is too smooth, too delicately spiced. They prefer:

amateur movies,

movies that are riddled with imperfections, or

older movies from when the machinery of illusionism was clunkier.

Rather than experience such a film as an immersive transmission from a glossy but very real reality, audiences may experience a shabby film like this in one or more of the following ways:

A story, better or worsely told, made into a precious moment by the crackle of the fire and the crackle of the storyteller.

Some people who got together and did a thing.

The recording (and reassembly) of a guided occurrence in space and time.

A show we put on for you.

A bit like a beat music combo.

Starting out, Guy Maddin went so far as to assemble his crew in the image of the “bad basement band.” In this, he was inspired by the “amateur acting” and neglect of standard filmmaking conventions in L’Age D’Or (Director: Luis Buñuel, 1930).

He was also inspired by the bad basement bands of his milieu. But when Maddin showed these bad basement bands his bad basement movies, they didn’t get it. They wanted Raiders of the Lost Ark (Director: Steven Spielberg, 1981).

For now, the realistical fallacy maintains its grip on cinema culture at its broadest.

(Cf. The Quality Imperative.)

Lens flare

Lens flares are often used to broadcast the (false) authenticity of shots that position the camera in outer space.

The idea here is that this shot of outer space is:

Too real,

Too profoundly subject to the universe’s physical laws and the arrangement of local celestial bodies - and on a 1:1 scale,

Too real, massive, and infinite to be caught on camera.

So real, in fact, that even the most slick, professional, and high-budget production cannot help but let slip that a film is a camera play and not a virgin miracle of the corporate entertainment complex.

The flare patches over the fact that this awesome screen presence was actually played by a tiny digital or cardboard looky-likey. A model shot. Poor looky-likey!

It’s been a long lesson today, thank you for sticking with me. Nearly there.

In theory, a lens flare is the sun breaking the fourth wall. It is cinema’s answer to guitar feedback; but rather than communicating the raw humanity of a flesh, blood, and soul artist, it approximates the vast untameability of the universe.3

The sun’s wild talent is so formidable that the audience doesn’t even question it when it misses its mark. Nobody leaves the multiplex saying, “slick movie, but did you notice when the sun banged into the camera? A $200 million budget, and they couldn’t get that right. Shabby!”

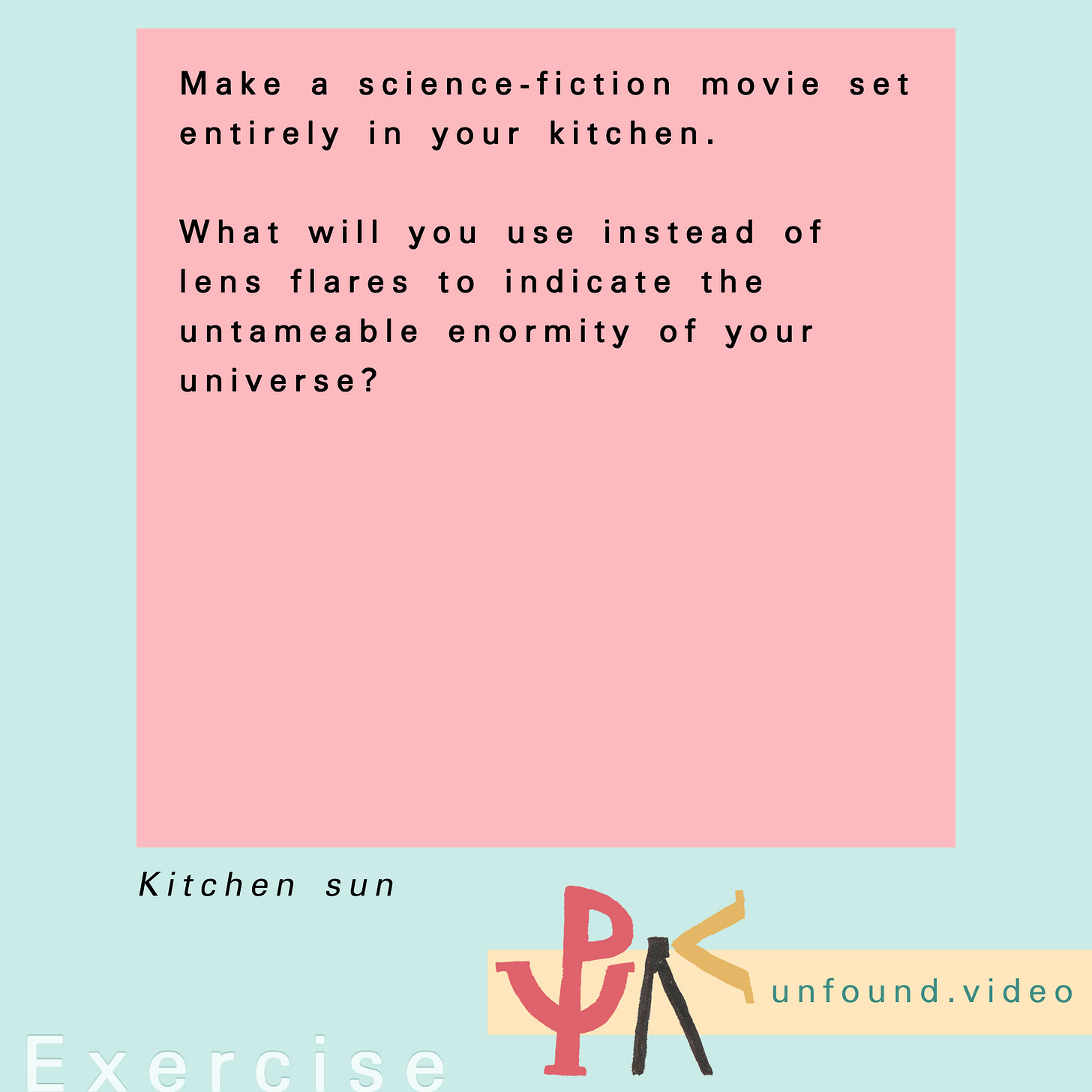

Exercise: Kitchen sun

Please share your thoughts, queries, and exercises from this week’s lesson in the comments.

Home time

It’s been a long one. Let’s not loiter for too much gossip today. But do look out for Don't Keep The Wicker Man Waiting. An exhibition of rare Wicker Man stuff, including “designer Seamus Flannery's personal schedule, set-build blue-print plans and photographs.” Perhaps the defamiliarisation this over-familiar picture needs. At the Horse Hospital in London from Friday.

Next week we’ll learn some behind-the-walls truths about home movies.

Class dismissed!

~Graeme Cole.

(Principal)

🐦 Twitter | 📸 Instagram | 😐 Facebook | 🎞️ Letterboxd | 🌐 Website

In the cinema lobby, it’s quite a different case. At that stage, the supposed auteur becomes ripe for analysis. However, analysis of the filmmaker’s clumsiness is usually reserved for technical assessments and general put-downs rather than emotional deconstruction.

There are persistent exceptions. The so-called mumblecore movies may be the bad basement band of the cinema. Without losing the benefits of being considered more or less normal.

In mumblecore, the membrane between the crew and the picture is a little thinner than in standard independent film. More or less authentic production flaws indicate that the writer, AD, cinematographer, etc. occupy the same sweaty universe as the film’s characters. The technicians’ feelings, experienced in a real life that takes place just behind the rented walls of the set, are allowed to feed into the filmed lives of the characters through scratchy lapel mic placement, conspicuous continuity error etc.

However, the characters are not allowed to mention these flaws to each other. The actors are not permitted to give a “shout out” to the crew. Only the on-screen animals are permitted to tilt their heads at these otherworldly manifestations.

Meanwhile, lens flares in Earth-set movies approximate the vast untameability of the inner universe. The sun is too big vs. the truth is too big. The lens flare conveniently patches over the filmmakers’ inability to cinematise the truth - if they even know it!